When the Brain Relearns How to Connect

What a new Cell study suggests about psilocybin, plasticity, and why context matters…

For years, psychedelic research has leaned heavily on a single word: plasticity. Psilocybin, the shorthand goes, makes the brain more flexible. Old patterns soften, and new ones become possible.

A recent paper published in Cell doesn’t reject that idea, but it does narrow it considerably. What it shows is not a brain suddenly awash with possibility, but one changing in specific, conditional ways. The effects are patterned, selective, and contingent on what the brain is actually doing at the time.

That caveat does a lot of work.

Plasticity, with terms and conditions

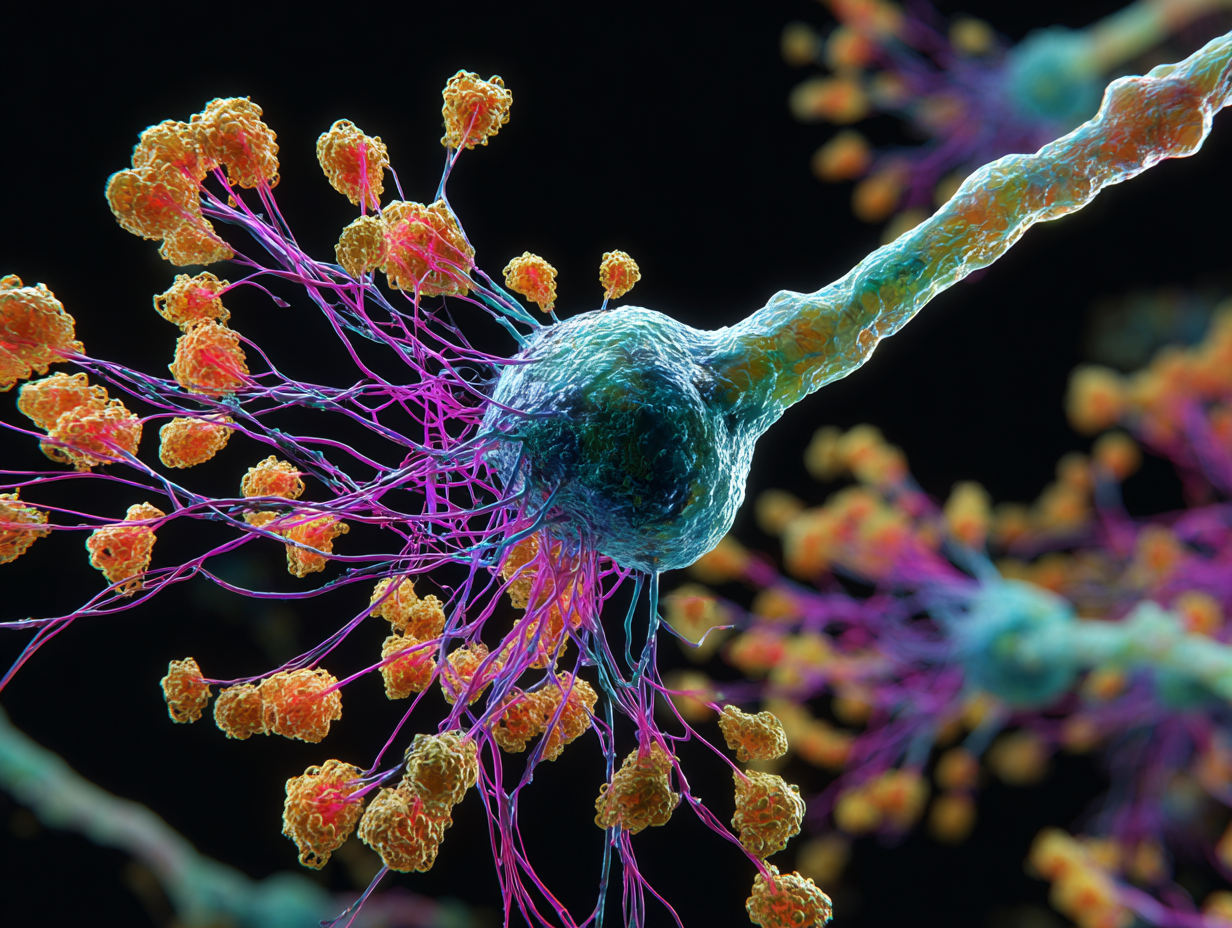

Using whole-brain mapping in animal models, researchers looked at how neural connections changed after a single dose of psilocybin. The results were quieter than the popular narrative might suggest. There was no explosion of new connections and no sense of the brain being broadly rewired all at once.

Instead, existing pathways were adjusted. Some became more influential, others faded slightly into the background.

The changes remodeled existing, familiar routes through the brain rather than spreading evenly throughout it. It looked less like expansion and more like rebalancing. Think of it as a city: no new roads being built, but traffic being redirected.

One of the core findings was that the process is activity-dependent, which in neuroscience, refers to the principle that structural change occurs only in circuits that are actively firing. When researchers deliberately reduced activity in certain regions while psilocybin was present, the expected structural changes did not occur. Lasting reorganisation was seen only in circuits that remained active during the experience.

So what does that mean in practice? If someone takes psilocybin while feeling sad, will the drug fix the emotional state?

That is an unfortunate no; psilocybin does not fix or reinforce a single emotional state. What it does is make active neural circuits more open to change, for better or worse, depending on what unfolds during the experience.

Think of it as a city: no new roads being built, but traffic being redirected.

When mental loops loosen

One of the clearer patterns involved mental feedback (or cortical) loops. These self-reinforcing circuits, often linked to repetitive thinking and a strong focus on the self, tended to weaken. In particular, brain systems that repeatedly cycle self-related thoughts became less dominant.

For example, the brain network that supports self-focused thinking, daydreaming, and rumination became less active.

At the same time, circuits involved in sensation and bodily awareness became more prominent. The brain appeared less trapped in its own internal feedback and more engaged with what was being seen, felt, and sensed.

This matches how psychedelic experiences are often described: less mental chatter, less fixation on the self, and more attention on perception, feeling, and the immediate environment.

The study doesn’t explain the experience itself, but it does help clarify why that shift might occur.

Why the effects can linger

Another key point is how long these changes lasted. The altered network patterns remained well after the drug had left the system.

This helps explain why a single psychedelic session, especially when well supported, can have effects that carry on for weeks or months. The experience may be brief, but the brain doesn’t simply snap back to its old configuration once it’s over.

Rather than acting as a temporary mood lift, psilocybin seems to activate a phase during which the brain is more receptive to reorganisation, allowing certain patterns to settle into place once that period of remodelling closes.

Why context really matters

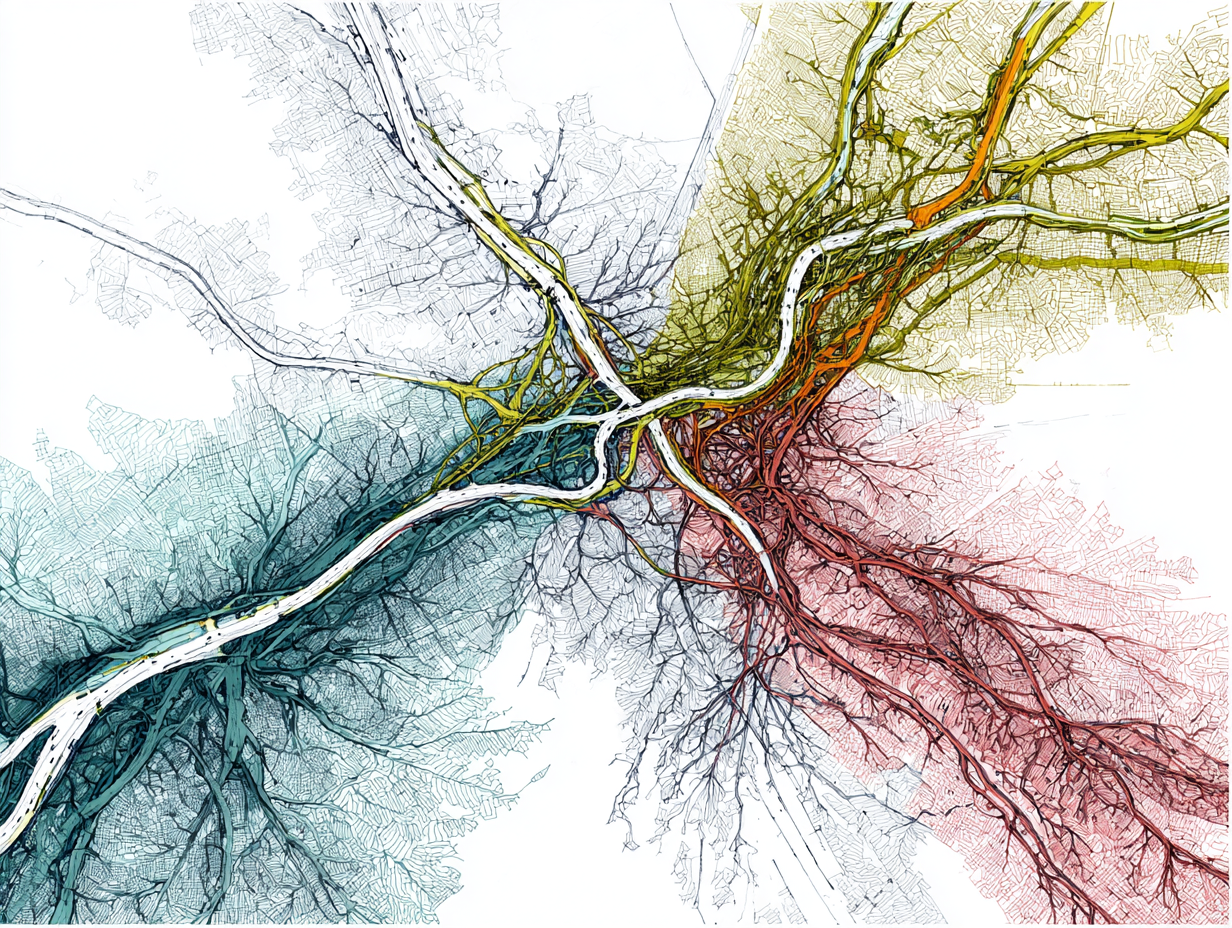

Context isn’t just psychological framing or cultural tradition, it shapes which circuits are active while the brain is most open to change. Set and setting take on a more concrete meaning.

What someone pays attention to, how safe they feel, what they’re sensing in their body, and who they’re with all influence neural activity. If change follows activity, then these set and setting factors play a direct role in what gets reinforced and what begins to loosen.

This also reframes integration, which is often talked about as something that happens after the experience, a process of making sense of what occurred. The study suggests that what happens during the experience itself may be just as important in shaping longer-term outcomes.

Fewer big claims, clearer mechanisms

What makes this study useful is its ability to track physical changes. Rather than claiming that psilocybin makes the brain “more plastic” in some broad or mystical way, it shows how that restructuring happened.

Psilocybin doesn’t install a new structure in the brain. It temporarily relaxes the usual constraints, allowing ongoing patterns of activity to reorganise how networks are weighted. Where things land depends on what the brain is engaged with at the time.

It’s a quieter story than some headlines might prefer. But it’s a more practical one that allows us to consider more deeply the value of psychedelics and the implications of set and setting.

Read the full paper here.